Important: Everything Is Stories is created specifically for listening and is best experienced audibly. If you have the means, we highly recommend listening to the audio version. It captures the emotions and emphasis that cannot be conveyed on the written page. Transcripts are produced using a mix of speech recognition software and human transcribers, so there may be some errors. It is advised to refer to the accompanying audio for accurate quotes when using this content in print.

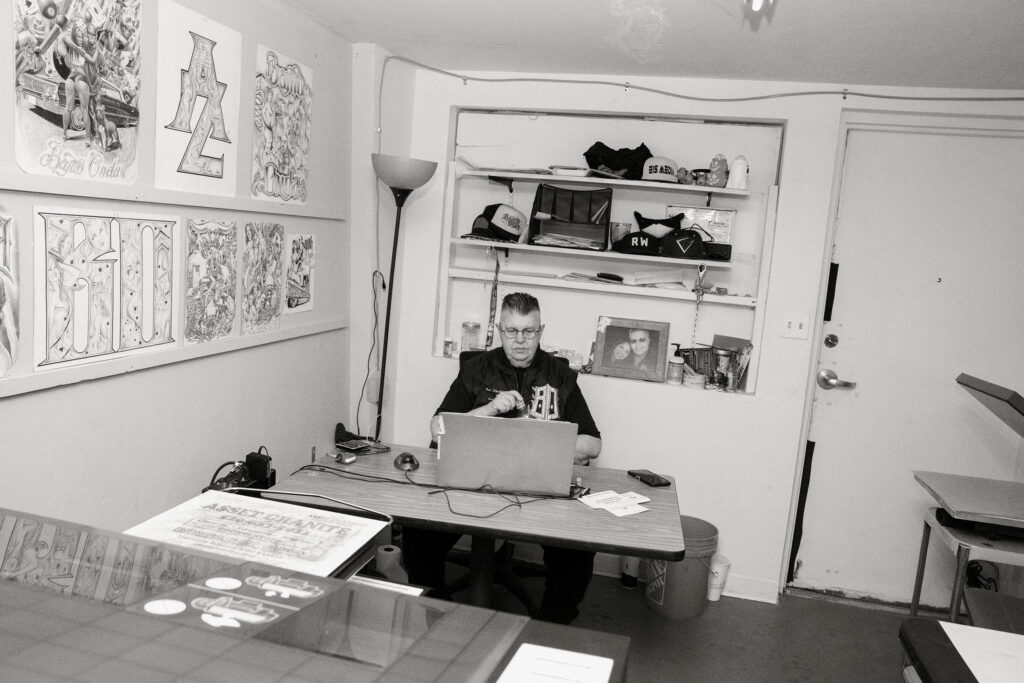

DEL HENDRIXSON, JR.: So we’re in my studio right now and we’re looking at prison art from my collection. My art collection is a collection of people that even though they’ve been in prison for decades and decades, they wanted to show their talent to the world. And I always have featured them and the artists, and they have sent me some miraculous stuff. It’s for people to believe that they have a voice, they have a face, they have talent, and their art is valuable. They’re all in for murder, you know? That’s it. You get life sentences for murder. You know?

I think I have around a hundred pieces and I can get another hundred in a week if I wanted it. The artwork to me represents a struggle. It also, if you ask people what do they think of when they think of prison, and they say the bars, the cement, the guards, they never say the faces of the people. To me, it represents their struggle. I’m the curator, I guess.

There’s mainstream and there’s the underground. I operate in the underground that is expelled from mainstream. When people fall outta mainstream to the underground, they’re shocked. They don’t know how to swim in this underground world. But underground doesn’t necessarily have to mean negative. It could just mean dropped out of society – don’t want to deal with mainstream society and all of its bullshit. I choose not to be part of mainstream. I would rather keep my society private. I created my own society because I knew I could not make it in mainstream.

My name is Del Hendrixson, Jr. It’s actually junior, it’s my birth name, and I’m proud of that. It distinguishes me. I founded Bajito Onda Community Development Foundation to educate, not incarcerate, to provide training and skills to people that have been excluded or rejected from society. It’s a program that is a working model to help people like me that have been in prison and never really felt comfortable entering mainstream society. My choice of helping people is to work with the people that are hardest to reintegrate into society or to help them have their own businesses without even having to participate as a working member of society. I’m in Tucson, Arizona, and we’re in one of my creative studios.

I grew up with one ear ringing and the other ear stopping the ringing, you know? And what went on in between was chaos. I constantly fought with my father the whole time. My dad was an army colonel. He was strict as hell. He beat the shit outta me all the time. He was kind of a punisher disciplinarian. Do I think he was fair? Probably not. I think he was very aggressive, reactive, and I think he took a lot of his anger and pain from World War II out on me because I was there. Of course, I didn’t know how to act, so I mouthed off a lot and I got my head knocked off a lot, but I still loved my father. He was my role model.

He was trying to throw me out of my old life and I told him, I’m not leaving till I’m 18. You’re stuck with me. I stayed in Hot Springs. This is where I was raised. Hot Springs, Arkansas. It’s the home of Bill Clinton. I actually went to high school with Bill Clinton. And we called him Billy Clinton.

Back in the day, I was horrible in school. The only thing I excelled at was psychology and I think that’s because I was crazy before I graduated. The counselor told me I only had two choices for a career, and that was to join the army or go to prison. I said, that’s a little rough, don’t you think? Everybody else was getting to be like a doctor or something. But I ended up with those two, so I don’t know whether they just didn’t like me or what, but I figured, what the hell? I’m not gonna let it stop me.

I had made up my mind a long time ago I was not gonna go to the army, so I thought I might as well look forward to prison. It was kind of a joke back then, but then it turned into not a joke.

My best friend Woody lived in Little Rock. We had become friends right after I graduated. When I met him, he was like as big as a mountain. He was a force. But the thing about him was his mother had made him eat everything on his plate his whole life. So he ended up weighing 300 pounds when he was very young, but he only had one hand. So he was born with no left hand, he was a thalidomide baby.

AUDIO CLIP: Thalidomide. The wonder drug was introduced in 1958. Its advertising said how safe it was in its varied forms. It would take away your headache, put you to sleep and calm you. Two and a half years later, the drug was withdrawn after reports of deformities and newborn babies that are some children without arms, some without legs, some without arms or legs. In 1972, the silence was finally broken. We acknowledge both the physical hardship and the emotional difficulties that have faced both the children affected and their farmers.

DEL HENDRIXSON, JR.: He just had a nub right there and some little fingers, but it didn’t stop him at all. He just rolled right along. He was a jolly guy and he was very protective of everybody around him. We just started hanging out together nonstop. We couldn’t live without each other. We were like, man, this guy is exciting. And he thought I was exciting, you know? And everybody else was just a drag. And we were like, “Man, where’s the world? We need to jump into it.”

We both rode motorcycles. We both raced cars. If it was exciting, man, we wanted to do it. He used to call himself wonderful Woody and he used to call me Dangerous Del.

I graduated in ‘65, so it was probably 1966. I knew someone that worked at the newspaper and so they got me a job there. I thought it was cool cause I’d never had a job. I was totally fascinated by graphic design, the photograph, how it went from a photograph to a galley proof, and then they had a dark room.

So they took me into the dark room and they showed me how the cameras worked. It was really interesting to me. It was just such a fascinating world. I hung out with the people that worked in the dark room. They said, “If you ever need to change your birthdate or get an ID or do something, we’ll show you how to do it.”

What I wanted to do was go to clubs and I was too young. Then the guys told me, “Oh, we can make you a birth certificate and you can become 21.” And I said, “Okay, cool.” I could go to clubs. So they made me a birth certificate, saying I was 21.

PRODUCER: Did they ever explain why they were making birth certificates?

DEL HENDRIXSON, JR.: Well, no, I mean, they just said they had the talent, you know, and they said you need to be 21 so you can go to clubs. I think they took my birth certificate and then I gave it to ’em and they made a copy of it. And then they reduced it and they made it black because my real one was black and reduced and it had white letters. So what they did was they reversed it, so it was a reduced reversal on black paper with white ink. I guess they had a seal, so they stamped it with a seal that made it just so legit. I took it into the driver’s license department in Arkansas and I said, “Oh, excuse me, ma’am.” I said, “You made a mistake on my driver’s license. I’m 21.” So I gave her the thing and she’s like, “Oh honey, I’m so sorry. Let me fix that for you.” So then I became 21. It was so easy to do and I was like, is that all there is to it for people to believe you? And so that’s what led me to become a really good graphic darkroom technician.

I could even take like a negative, it didn’t have lines on the paper, and I could take an x-acto knife type thing and I could scribe the lines to make a form. And then I just became so fascinated in everything. I wanted to know everything about it. Then I got fired.

It was on a Saturday. I wore shorts to work because I didn’t think I needed to wear regular clothes and my boss saw me at the bus station and he had a fit and he fired me. I was like, “But it’s Saturday.” I said, “Why can’t I wear shorts to work?” So he told me, “Well, you’re fired.” But I thought he was kidding.

So I went into work anyway and he’s like, “What are you doing here?” He said, “I fired you.” And I said, “For wearing shorts?” I said, “Who cares?” But anyway, he did fire me and I was pretty heartbroken, but it kind of set into stone that I would become from then on trying to crawl my way into some other kind of printing. I decided I gotta get out of that town.

Hot Springs, Arkansas was like 30,000 people and it was just nowhere. And this didn’t look like anything I wanted to be a part of anymore, and that couldn’t see me going and trying to find another job because it wouldn’t have been fun. So I told Woody, I was like, “Man, we’re gonna have to get the hell outta here because if we don’t, we’re gonna end up stuck here. We’re never gonna get out. We gotta go experiment, you know, adventure.” And so he agreed and we just set out on our own to go discover the world.

So we decided to move to Dallas. We used to road race, little race cars up and down the mountains in Hot Springs. And so we met some guys from Dallas and they said,”If you ever want to come down, we got you.” You know? “We’ll let you stay with us too. Get settled.” We took ’em up on it and we went down there.

I thought Dallas was gonna be like cows. I mean, seriously. I thought there was gonna be like cows walking down the street. I thought the road was gonna be like dirt. I thought it was just gonna be like the wild west, but I let my parents know that I was gonna get out. And my parents were so mad. My father, of course, he was crying when we pulled out the driveway, and then my mother, she just couldn’t believe I was really gonna leave.

We took almost nothing with us. We didn’t even have hardly any clothes or anything. We had never even been to Dallas before and we moved in with those two guys that said we could stay with them. It was weird. I was like, “Whoa.” It was like clubs and pool tables and seedy people and just people hitting on us and stuff like that.

I used to make money playing pool, and so did Woody. We played pool all the time. We ran with some of the roughest characters in Dallas. We just kinda landed in their lap. All of them had been to prison, all of them. We ran around with those guys without even realizing who they were. Woody lived in a motel called, uh, Tower Motel out on Harry Hines strip and there was nothing in there but prostitutes and drug dealers and drug addicts and thieves and just all kinds of stuff. It was like a real seedy hotel with all these characters living there and everybody fell in love with us because we were such hicks, and they wanted to help us and take us under their wing and they did. So they became our first friends.

Woody and I were together for 27 years, man. I mean, we were down for each other and he took me on my first trip to Mexico, that was about 1967. I was 20 or something like that when I was in Mexico. I lived there for about a year. I had to get away from Dallas because there was so much crime and somebody had broken into my house and stolen my cameras and a bunch of my stuff. So I decided I’m not gonna put up with Dallas anymore. I’m gonna take off and go down there.

Monterrey, Mexico way back in the day was a beautiful place. I went to bull fights and I went to rodeos. I just went to all different kinds of stuff that we don’t have. I liked living in Mexico a lot. I liked the food. I liked the people a lot. I liked the fact that people were friendly to me because I was an American. That I was friendly to them. One thing about Mexico is that it taught me a lot about being an immigrant. I didn’t know how to go to a bank. I didn’t know how to count numbers. I tried to buy something. I didn’t know how to spell the numbers. I had to have people fill stuff out for me. I learned about Siesta. I still take siesta. I mean, every day, five o’clock, bam, I’m down. Eight o’clock I wake up, I’m refreshed. I assimilate as, I don’t know if you say, I assimilated the Mexican culture into me, and I realized what a beautiful culture it is.

I decided to leave Mexico and to go back to Dallas because my visa kind of ran out and then Woody was really missing me a lot, and then I was missing the way that we normally do things. First it was adventurous and then it was fun, and then it was discoverable, and then after that, it wasn’t fun anymore. I wanted to go back to the United States and take Mexico with me. It impacted my life living over there. It made me want to know more about the world. It made me want to know more about more people. After I figured out how to speak Spanish, I spoke Spanish continually. From then on, sometimes speaking Spanish only for years, choosing Spanish over English.

When I got back to Dallas, it was totally different. I was still into the party scene but it was more like trying to reestablish myself as something else. I needed a job and the only thing that I gravitated to was something to do with printing. So the first thing I tried to do was go to work at a print shop.

It was a big press, and they made a little magazine called Where, and it has the restaurants to eat at and the places to do and go. I worked under the art director. So the art director quit one day and they said, “Well, since you’ve been working under this guy can you put the magazine together?” And I was like, “Well, yeah, I can put the magazine together, no problem.” So I became the magazine publisher for Storm Printing and they were printing all over the whole country. And so I put the whole thing together. I was so proud of myself, but that’s how I learned to make a magazine.

I met this guy that was making a killing off of making ID cards downtown. That was about 1980 in Dallas.

He had like a little passport ID photograph place, like a little bitty building, but he had one of these Polaroid cameras and it was like a certain thing to make ID cards with. He contacted me and asked me if I could help him make that graphic for it. You typed their name and then you put it in the Polaroid and you took their picture and it photographed this background, and you slide this piece of paper in and it had the guy’s name, address, and height and weight and everything.

So I slid it in there and then I took a picture and it photographed this card as well as the guy’s picture. It all came out in one little ID card, laminated. So I thought, okay, I can make the ID cards, I can laminate ’em and I can fill ’em out and put the guy’s picture, put his name in everything, and I can put a Texas ID card, but I didn’t put an official Texas ID card.

What I had done was I had learned how to make these ID cards from my friend, and he was downtown and I was on the other side of town. I figured, well, I’ll just kind of do the same type of business. I made the small little building and I made it an ID card center. So I started making these ID cards because they were totally legal, there was nothing wrong with making an ID card. But then as I made the ID cards, the Mexicans started asking me, “Can you make me a Social Security card?” I said, “Well, I don’t know. Let me check.” So I thought, well, let me call up Social Security and ask them if I can make one.

So I called up, I talked to some lady, I never did get her name, unfortunately. I said, “Can I make, uh,” because I was kinda like leery about it, but I said, “Can I make Social Security cards?” And the lady said, “Sure, just don’t put anything on the back of them. Just make a copy of your social security card.” So I thought, okay. But then a little Mexican guy comes in and he’s wearing a big sombrero and he’s got a mustache and he only speaks Spanish, and I speak Spanish. He did not have a Social Security number,he did not have an ID. He was definitely from Mexico, definitely illegal. And he says, “I’ll pay anything for a birth certificate. I really need a birth certificate so I can go see my sick mother in Mexico.” And I knew in the back of my head that I had this talent to make birth certificates, but I didn’t want to think about it. And I said “No, no, no, no, no. I cannot make no birth certificate. Absolutely no, none. Done and done. Goodbye.”

So he came back like five times and every time he came back he offered me more and more money. So the more he came back, the more I felt the pressure. I felt guilty because I could go back and forth across the border because I was an American and these people were building this country and the roads and the babysitting and the gardens and the everything, and they could not go back to Mexico. Once they were here, they were stuck here. I felt it was very unfair. So what I did, I considered it then sort of amnesty before it’s time.

After about the fifth time, I said, “Look, I’m gonna make one birth certificate just for you.” I took his information and what I did was I made it with a different, I think I reversed his birthday or something. Instead of June I put January or something like that so he can still remember it. It was still him, but it kind of wasn’t him.

And so everything then tied together. I made him a birth certificate, a copy of one. I made it just like we had made in Arkansas and then I ordered up a seal from an office supply store. I wanted it to be legit. So if it was gonna be illegal, it was gonna be legit illegal. That was the kind that, the embossed, so you could seal it, you can actually feel on the surface of the paper, this impression. Well, nobody’s gonna try to read that. Nobody’s gonna try to question it because it’s black, it’s got white letters and now it’s got a seal on it. So everybody was like, this has gotta be real. So I gave it to him and he gave me like, I don’t know, a hundred dollars. He was practically in tears.

So he had a picture ID, he had a social security card, and then he had, uh, a birth certificate. Nowadays that would never fly because that was just a piece of paper back then. But back then they did not have all the sophisticated scanning or hologram or threaded documents or anything like they do now. So then he had three more friends that needed birth certificates and I was like, “Oh, hell no.There’s no way.”

So then he offered me money again, but I had already made him one, so now I was already guilty. So I said, “Okay, bring me the guys, I’m gonna make you three more.” I wasn’t really charging maybe a hundred dollars, $125.

I had been making these birth certificates for people and then one day this lady and this man came in and they were wearing coats, long coats in July in Dallas. It was hot, sweaty, and they wanted to come in, they wanted to talk to me. They wanted a copy of a social security card and they wanted a copy of, uh, ID card.

So when they came in, it was so hot. I was like, man, these people look kind of strange. And they had, their arms were like stiff out, like down at their side and I thought, this smells weird, you know?

So I said, oh, I’m not gonna tell these people anything. So they asked me, they said, “Can you make us an ID?” And I said, “Yeah.”But what really was weird about ’em was that number one, it was so hot, they were wearing these coats. Number two, when I asked them what their height was, what their weight was, they told me in inches and pounds, not in centimeters. And what’s the other thing? Kilograms. Yeah. So they told me in English and I thought, that’s not right either, cuz a Mexican would’ve known the other one.

When I told them, they said, “Well how about a birth certificate? Can you help us out?” I said, no, I don’t make birth certificates. I said, “You have to go down to immigration for that.” No matter what I told them, they just kept on and on and on. Finally, I made ’em an ID card. I gave it to ’em, and in the back of my mind I knew something was fishy with those people.

About two weeks later is when they came back in force. I heard this knock on the door and it was too loud. I mean, it wasn’t just a knock, I thought, Hmm. So I told this kid, I said, “Open the door. Some people are trying to come in.” I’m sitting there at my typewriter. It was literally a little old typewriter actually. I was typing out a birth certificate when they came in. I had exactly 111 Social Security cards. They were ones that I had printed. Nothing was on the back, but there was these Social Security cards. I had those and then I had like 20 birth certificates. When they knocked on the door, I took the birth certificate that I was typing on and I just picked it up out of the typewriter and I stuck it underneath the typewriter, like they weren’t even gonna look there.

And so when they open the door here, they come in – just a big stream of agents come in. Sure enough, man, I mean, they came straight for the typewriter, straight for me. They got guns, they had rifles, they had pistols. And then they grabbed me by the neck and they threw me down on the floor. I counted 22 people with guns aimed at me. I also had a bladder infection, so my pants were unzipped. So when they threw me down, my pants just about fell off

They come in there with these guns. I mean they had the biggest guns, rifles, guns, everything. 22 of these people, there was like seven immigration cars, cop cars, sheriff’s cars, everything outside my place. I was like, “Oh hell.”. They start searching the whole place. They take my file cabinets, which I had more shit in. I just had birth certificates everywhere by then. So I’m down in the middle of the floor and they’ve got these guns aimed at me like I was Al Capone. They handcuffed me. I’m laying down with my pants falling off. And they’re piling all this paper and shit on top of me. And after like an hour of all this searching and everything, they told me to get up, they actually picked me up and I asked them, I said,”Can you please just zip up my pants?” And they yanked me up and they marched me out of there. They put me in the back of a immigration vehicle, the green immigration car, and they locked me up in the immigration cell. They wouldn’t feed me, they wouldn’t give me water for at least 10 or 12 hours. I was like, are you kidding me? Really? I’m this important?

So I got arrested on August 4th. By October 29th I had had my little hearings and I was officially sentenced. The judge said, “I hereby sentence you to three years in prison.” And man, I felt like somebody had just dumped a bowl of spaghetti on my head. I felt like everybody was looking at me. I felt like there was nothing I could do. I had just made this big fucking mess of my life and now I had to face whatever it was that I had no idea I was gonna face.

So the fear of going to prison is just as bad as going to prison. Prison is really bad. I mean, it’s not anything I would ever wish for anybody.

I reported to prison on December 27th. They have a thing called Sally Port, and that’s where this door, this big, heavy steel door comes clanking over and then you get in the middle of it between the next door and then that one clanks open and this one clanks shut.

My mother and my girlfriend went with me, and when I turned around to say goodbye to them before I knew it, this door was closing behind me. When I looked out, after the second door opened, I could see the courtyard.I was taken and photographed. You become a number. You don’t have a name anymore. My prison number was 12605 -707. It’s all dehumanizing. Everything that you had on the outside, it becomes stripped away from you every single minute. By the time I got up on the unit that I was gonna be on I was really in shock and it just became a nightmare.

I was in there with men and women and that was strange enough from the minute I walked in there. it seemed like the sky on top of the place was never happy again. It seemed like it was just a gray cloud over the place. I didn’t see how people could laugh in there and be joking and everything. I thought these people are sick, but people did carry on their lives in there.

I tried to do everything I could other than think about being in prison. I wasn’t prepared for all the little mind games and the games that people pull on you. They really were on me a lot. It’s like you’re locked up with these people. There’s 1200 people to choose from. A lot of them choose you. You don’t choose them, but they choose you, and if they choose you, then you can have a big problem.

It wasn’t violent in the beginning until they get to know you. The first day there I was told that because I spoke Spanish there was someone there that needed a translator. That person was this little heroin dealer from El Paso and she hit on me the very first day. So this lady, she asked me if I wanted to go watch TV with her. So I said, “Okay.” But when we got in the TV room, she took her clothes off and she wanted me to touch her. And I said, “Oh, hell no. Not first day. Not last day, no.” So then she actually went and snitched on me and told the guard that I had touched her. And so I got in trouble from day one. I got like a 24 hour watch on me and it never stopped the whole time I was there.

The guards controlled everything. They controlled whether you could talk on the phone. They controlled Who was watching tv. This one guard, he told me, he said, “You know what’s wrong with you?” I said, “What?” He says, “You’re not programming. You need to program.” He kept looking in my face and he kept telling me to program. I said, “I don’t even know what that means. I never heard that before.” But what he meant was he wanted me to roll with it. I go up to the guard and I said, “Look, you gotta help me. Why is it that everything happens to me? What can I do about it?” He goes, “You have to get mean.” I said, “What does that mean?” he said, “Look, you need to get violent. You have to let people know they can’t fuck with you no more. You need to stand up for yourself and quit being a pushover. The next time somebody pisses you off, you just need to go off on them.” And I thought, well, I haven’t tried that.

There was a person in there that used to sell sandwiches and her name was Peggy. I used to tell her, I said, “Peggy, how is it you don’t have to go to these meetings every week with the warden and watch him on tv?” And she said, “Come here” She said,”I’m gonna tell you the secret. The quicker you act crazy, the quicker they’re gonna leave you alone.” So I said, “Uh huh.” So everybody thought she was crazy but she really wasn’t. I said, “You know what, I’m gonna take your advice.” So from then on I just acted crazy. I mean, if somebody told me I couldn’t wash my clothes because they had to finish theirs, I took theirs, I threw ’em out on the floor just to start problems. If somebody wanted to fight, I was ready to fight for no reason at all. I wasn’t gonna take no more shit off of anybody. The unit manager told me if I didn’t straighten up he was gonna send me to another prison. So I took my hand and I slammed it down on his desk and I said, “You’re not gonna send me anywhere.” I said, “You’re gonna shut the fuck up and treat me like you treat other people that are not afraid of you.” From that day forward, he stopped.

Every time I had an opportunity to do something to somebody, I fucked with them. When you’ve been in prison you realize that your body is in prison but your mind is actually free. So you can think about anything you want to think about. If somebody pisses you off you can actually create mind movies where I would just kind of reach out from within my eyes actually looking at somebody, and then I could just reach out and then either kill ’em or beat ’em or cut ’em, or do whatever I wanted to do to him very violently and I hated it. But at the same time, it gave me the satisfaction of dealing with the people that were controlling me. So my body stayed still for the prison requirements, but my mind just began to film all these movies about violence and what I was doing to people that pissed me off. So that’s how the violence starts.People just spring off and then they hurt people really bad in there.

There was four phones on the wall. I was trying to get a phone call out before 11 o’clock at night to my girlfriend. I told this guy out there on the phone, I said, “Look, I want to use the phone before 11 o’clock.” And he told me to go fuck myself. I said, “Okay, if you tell me go fuck myself, I’m gonna go tell the guard. there’s a fight at the phones.” So I go tell the guard, “There’s a fight at the phones.” He was a huge black guy. I mean, he weighed like 350 pounds. So the guy turns around and he tells me, “Yo mama ain’t nothing but a piece of white dog shit. And I said, well, at least she ain’t a fucking n___”

So man, that was like, it was on. So then the guard was black, the captain’s black. The only guy that was white was the lieutenant. And he told me, “What did you have to say that word for?” I said, “Well, I just lost it.” After you’ve become violent, you get what you need. Get what you want in prison. Get people to leave you alone. Nobody prepares you for when you step outside the same doors that you went in. And so when I got out, man, I was very, very, very violent.

PRODUCER: There’s the one thing about being violent and then one thing about being racist.

DEL HENDRIXSON, JR.: I mean, my mom is not a piece of white dog shit. There is no niceties in prison. You say whatever you wanna say, you get over it, or you get in a squabble and that’s it. None of it makes sense. Prison makes no sense. You’re in there, you’re under pressure. You’re with racist people. I mean, they were racist too.

PRODUCER: But the story that you told us before is that you were saying you were becoming more and more violent. But there’s a difference between violent and being racist.

DEL HENDRIXSON JR: There’s no difference.

PRODUCER: There’s a huge difference. Like a lot of people can be violent and not have to say that to someone.

DEL HENDRIXSON, JR: Mike, That’s what I’m saying. But how come he can say, my mama is a piece of white dog shit?

PRODUCER: They’re not even, they’re not even on the same scale. You can’t corral those as even close to each other.

DEL HENDRIXSON JR.: Well, whatever.

DEL HENDRIXSON JR.: All in all I did 11 months in prison. I got arrested on August 4th. On August 8th, Woody got arrested. Neither one of us were expecting to get arrested. He got arrested for selling drugs, cocaine. I got arrested for counterfeit documents, so we were both in the soup together. We didn’t know what was gonna happen.

I ended up getting sentenced to prison, but because he was so damn fat, he weighed like 500 pounds by then, he got probation and so he didn’t have to go to prison. They said they didn’t have a uniform for him, they didn’t have anything for him to wear.

When I was in prison Woody kept up with me. He came one time to see me, but then after that, because of his case, they wouldn’t let him come back. But every time I called him he accepted the phone call where my family, every time I called them, they wouldn’t accept the phone call. Everything started to divide up and really caused me craziness.

My first day out of prison I went to a halfway house called Volunteers of America. Really, I should have stayed in prison because I wasn’t prepared to try to be out yet. Nobody had prepared me or anything. I felt like I had just been mentally whipped and stripped.

You know, Woody had met me and bought me a pizza. Thank God for Woody. He took me to buy clothes, kind of assimilate a little bit. It was awesome to see Woody again. He was my biggest joy and he was trying to be supportive, but then he also had his case that he was trying to work out from under, but we were sidekicks again, but I felt like they had just wiped my slate clean. I couldn’t remember shit. I couldn’t think. I couldn’t process information. It was horrible. I got very, very mad and I used to take it out on myself first. You feel so hopeless that you just want to take it out on somebody, but if you take it out on somebody else other than yourself, then you end up going back to prison and that’s the catch.

So instead of doing that, I ended up beating myself black and blue. After a while, nobody wanted to come near me. I scared him to death because of the way I looked. I was big. I was mad as hell and really full of rage. I remember one time I was in California and I went to a bathroom and somebody tried to walk in my stall while I was in there, and I just put my foot and kicked the door and busted them in the face. I didn’t have to do that, but I wanted to just hurt anybody I could, any way that I could.

When my father passed away, it was 1980. It’s a long time ago. He was my rock. I mean, he used to beat the shit outta me and make my ears ring and all that, but he still was my guiding light, and he was fair to me. But boy, he was strict as he could be, and he was an army colonel. So that’s where I got a lot of my discipline from. Believe it or not I was really controlled by him, but when he passed away it just destroyed me. My mother was never nothing to me, really. My sister wasn’t either, neither one of them was nothing, but he was everything, and I was his favorite. So when he died, I mean, it just shattered my whole world. So I just decided from then on, it was just me, but I didn’t have his wisdom, so I was just kinda like, just fuck everything, you know?

It was really hard for me, so I just didn’t care about myself. They tell you that no matter what you do, no matter where you go, no matter what you try to do, you’re always gonna be branded that prison number. And you know what? It’s true. I’ve tried to rent an apartment. They said, no, you have a criminal background. I tried to get a job. I had gone around to some printing companies and they would tell me, fill out the questionnaire. Have you ever been arrested? Yes. What was the outcome? I went to prison. Ugh. Well, we’ll call you. Don’t call us.

So everywhere I went, I was turned down again and again and again. Finally, I decided to start my own business. I just figured that I would start learning how to print myself. I started making money. I started working really hard, but I still wasn’t able to be integrated back into society. It’s a constant mental challenge to try to control your body because after being in prison, your body is controlled by prison. When you get out your body is free to do all kinds of shit, but your mind is trapped, so it’s the opposite. I would have tremors all night long. My body would never rest and I could never sleep.

I had learned to make money. I had learned how to print legal things, not birth certificates, T-shirts and caps and all that. I was doing really great but I was miserable and I couldn’t get out of it. My head felt black. I felt like I didn’t have any purpose. I felt like I didn’t have any reason to keep exhausting myself trying to make money. I just didn’t know what to do. Money could not buy any calmness in me.

The feeling that I had, it just kept building and building and building. I woke up one morning and I just decided I really didn’t care if I died or if I got sent back to prison. I thought I could spend the rest of my life in prison or die, and it wouldn’t matter. I just wanted to get out of this free world thing because I wasn’t successful at it and I figured I don’t have anything else to lose, so I’m gonna go kill as many people that have made me miserable as I can get to. And then if I get killed in the meantime, oh well, I don’t care.

I had a list of like 50 people I wanted to kill. This one day I called my neighbor across the street. I loved this lady. And I said, “Look, Alicia, people are messing with me and I need something to protect myself with.” So she brought me over this Uzi right away. In that neighborhood everybody had guns, legal or illegal, because over there if you say you need help the neighbors come and help you. And she brought me this Uzi and she said, “Don’t worry about it, it’s loaded. All you have to do is pull the trigger If anybody comes in on you.” She left me with the gun.

So I was in my dark room where I developed screens, so it was pitch black in there. I said, “I’m gonna open the door and I’m gonna take off and I’m gonna go out and shoot people and run as fast as I can and get to as many as I can.” When I went to reach for the doorknob, which was to my right, and about two feet over, I stopped crying. I kind of just opened my eyes up and I saw this little white light coming through the wall of my print shop and I thought, “Wow, that’s really weird. I’ve never seen a light coming into my dark room.” I looked up and I saw this little, like a toothpick of light. But what happened was it struck me right in my chest, like a light coming into my darkness. I actually felt at that moment, a spiritual awakening of my chest and the rage and the darkness diminished. And at that moment I heard a voice. The voice spoke to me. It was over here to the left side of me, behind me, and it was like a voice of a wise man or a God or some kind of voice that affected me.

The voice told me, they said, “Stop. I want you to lay the gun down and I want you to listen.” So I put the gun down and that’s when my life just changed forever. It said, “You listened to man and you ended up in prison. Listen to me and see where I lead you.” And I thought, “Nah, I can’t be hearing a voice because that would mean I’m really crazy.” But then I thought, “Well, I’m really crazy anyway, so I might as well listen to the voice.”

And so the voice continued and it told me, it said “I want you to go and help people like you that are violent, abused, oppressed, thrown out, rejected, no purpose in life – because only somebody who actually has been there can relate to those people.” Then the voice told me, he said,”I want you to go and help young people not to go down the same road that you just crawled up from. They don’t have any life experience and they have no guidance. They’re just out here on their own.” And so I thought, “Man, why do I have to go help young people?” Cause I thought young people were just a waste of energy.

I started listening for that voice, and I’ve listened to the voice all these years. So everything I do is tied together with these visions or dreams that I’ve had that have come to me and told me what to do.

The way Bajito Onda got started is I took a picture, I started sending it into prisons. I started signing it, telling people, sending you love and hope and peace and whatever, and it started spreading. I started reaching out to the friends that were in prison of the people that I knew in the streets and they would give me names and addresses of prisoners, and I would write to them and I would ask them to send me positive messages of art.

And so I started getting all this art like crazy and I started making t-shirts with these messages on it, but it became a way for me to be a conduit to people that were lost in the darkness like I had been, and they were then spreading the message of peace and hope to friends around them. It just began to spread in prisons all over the country, as well as artwork from Thailand, Mexico, Brazil, Italy.

People started wanting to support the movement to educate, not incarcerate young people, and to give people hope when there was no hope in their life. The more that I sent to people and gave people t-shirts and things, the more those people started getting jobs, they started turning their life around. They started going back to college. They left the gang. They went to the Marine Corps or something. And so I just noticed this thing happening all over the country and in Mexico too. So every time I would try to give up, I would get a letter from somebody like in California. Saying, you have no idea how much this magazine meant to me. And because of this magazine, because of this t-shirt one of my friends has I turned my life around. I no longer disrespect myself. It was just crazy, the positive impression that came out of it. So it was like something that I wasn’t sure I really believed in myself, but I was doing what I was told to do, which is take messages and voices of people that didn’t have a voice or a face, and using it to talk to other people.

Sometimes when people get outta prison after 30 years I’m the first person they call because I gave them hope. So that’s how it began.

Woody actually, he started getting narcolepsy and he would fall asleep at the wheel. And then he would just fall asleep, period. And his air pipe would close off so he couldn’t breathe and his face would turn red. I took him to the hospital. He just kept gaining more and more weight and then he found out he had diabetes and he didn’t want to take the medicine.

So he would eat and eat and eat and then he would make me give him food. But I kept telling him you can’t eat this. And then he would fight me for the food. One day I was at work, I was printing in Dallas where I lived, and then I went home that night because he and I were living together. When I walked in, he was dead on the floor, so I found him dead and I called 9 1 1.

He just weighed 600 pounds. He couldn’t even get through the door. Took 13 firemen to get him out of there. When I lost him, it was like when I lost my father. I hated it. And then I really was all alone, you know, with the world. I never had another Woody, never had another Woody at all. No matter what it took, I was always right in his eye. He was always right in my eyes. So when he died, man, I was just like somebody had thrown me off a cliff.

In Dallas I started working with gang members. I started working actually with people that were on probation or parole. I wanted to start a charity. I managed to get a 5 0 1 charity and that allowed me to work with a lot of people that had to do community service. And in Dallas at the time, there was about 1500 people a month released from prison that had to do some kind of community service. And I took those people in and I allowed them to do community service with me. So more and more I became the center where the gangs, Texas Syndicate, Mexican Mafia, would come to me to do community service. And some of the cartels they had, people had to do community service. They would bring ’em to me.

I think they trusted me. I know they trusted me because I was crazy like them. I had been rejected by society. I didn’t give a fuck. I was gonna help them. I had a calling to go into prison after 20 years and it kept eating at me because I kept hearing all these people say, “Oh, we’re members of the Baptist Prison Ministry and we’re members of our church prison ministry, and we feel so good to go in there and pray with these guys.” And I thought, “Man, you’re fucking using these people as an excuse to feel good about yourself. You’re not doing ministry, you’re making yourself feel good.”

I got a ride out to Hutchins State Jail and I took the volunteer class, met the chaplain, I met a sergeant out there. They told me, “You know what we don’t have.?” I said, “What?” They said, “We don’t have nobody that can speak Spanish.” And so they let me go into the educational building. They said, “I’m just gonna throw you in there with a group of inmates and you’re on your own. We’ll come back and get you and see if you’re still alive in two hours.” So I said, “Okay. Done deal.”

I started going out there every single week and I started meeting with this group of guys, and I went around to the units and I picked the scariest looking guys, the biggest losers that I could find. I picked those guys so that I could put ’em in my group to see if I could help them. If you show some people that are very violent some kind of communicative respect, I think they respect you back.

I know when I used to go into prison, at Hutchins, they called it the bowling alley. It’s a long cement walkway. And when I would walk down there to go out to the chapel or to the education building, these guys would bang on the windows to tell me thank you for coming. They felt so grateful that somebody had reached back there behind there, that they would bang on the windows as a means of respect for me.

I have never been able to think like a woman, ever. To think like a woman doesn’t happen. So my father was a colonel and I was raised as a boy from the time I was three years old. I had an imaginary wife in Oklahoma that I went to see. I got kicked out of church for messing with girls and I had a flat top practically my whole life. When they wanted me to wear a bra, I was like, “Oh hell no. There’s no way I’m gonna wear that.” So I used to hide them in the attic, and when the electrician came down from the attic and he is like, “What’s all this?” I was like,”Fuck. Put that shit back up there.” You know? I was like, “That is for nobody.” You know? And then dealing with a period was like the most horrible thing in the world that I just never thought about.

It was like forced sexuality on me, like they wouldn’t even let me graduate in my class because I wouldn’t wear some little high heel things. And my name is Junior from birth. It’s not made up, but it’s just easy for me to be male instead of female. I don’t even think about it.

So my passport, my birth certificate, my driver’s license, everything is male identity. So that’s easy for me because I don’t wanna say I get more respect, but I’m just this way. I’m very strong. I order everything done. It has to be done my way or it’s not gonna work. And if I make the decision, it’s my decision. If I fuck it up, I fucked it up.

I’m happily married. I have a life. I live my personal life as me, but my public life is just, don’t worry about what gender I am. Matter of fact, in Dallas, a lot of people tell me, “You know, because of your lifestyle, you don’t get funding for your program.” And I’m like, “What lifestyle is that?” And they’re like, “Well, you know, you know, you know, you know.” And I’m like, “No. What is it?” “Well because of the way you live.” I’m like, “How do I live different from you?” You know what I’m saying?

I realized that if I’m not in control of me, then somebody else is gonna be in control of me – just the way it is. So yes, I’m technically SMI – SMI means “seriously mentally ill.” What that means is that when I came over here to Tucson my mental illness was identified. I felt it all these years trying to deal with it and the pain and the suffering of actually being mentally ill and not having anyone understand. It helped me a lot to come over here because I never really realized that I needed therapy until I came here.

So yes, I am a thousand percent bonkers. I don’t think normal, I don’t think right. But I’m very, very, very disciplined and that means a lot.

I think if people are crazy or called crazy or called mentally off, I think they need to be recognized and then reach out to them in a human way and say, “Okay, you don’t function like everybody else does.” In mainstream they told me I was crazy. I said, “Okay, I may be crazy, but if I stay disciplined and I maintain, and if people come in here and bother me or disrespect me or whatever, those people have to go because I can’t be around it.” Because if I become violent, then I become the victim.

My choice of helping people is to work with the people that are hardest to reintegrate back into society. Or to help them have their own businesses and make their own money without even having to participate as a working member of society, the more that we realize that we need to be successful, it’s really not that hard to work with people – then they become disciplined and then they become productive, and then this becomes therapy for them.